Update: the current version of this text was included as a chapter of Driving Design II, published by the Distributed Design Plaform. That version is available as a free PDF from their website, but there are some minor errors. I corrected them and made an edited PDF available here (13,4 Mb PDF) while the official version is not fixed.

Berlin, May 2023 (last updated March 2024)

"Protecting what's left is not enough

As the voracious chainsaw cashes in

We need to understand it's already enough

And replant the forest"

Gil + Gilsons - Refloresta

A few years ago, British author John Thackara was invited to present his book “How to Thrive in the next economy” in the USA. In his lecture, he urged humans to “think like a forest”. The book draws parallels between various movements in communities worldwide, weaving alternatives to design tomorrow’s world today, as Thackara puts it.

This vision of a common field encompassing multiple forms of action suggests that solutions to major contemporary problems should not be expected to come from a centralised grand plan. On the contrary, the way forward would be the complex and continued weaving of ultralocal initiatives that understand the conditions, culture, needs, and dreams of their immediate contexts. Naturally, each of these solutions has its obstacles and limitations, and that is precisely why it is necessary to find ways to create bridges of communication and understanding – connections – between them. Thackara’s book is an attempt to build those bridges.

I was reminded – once again – of that talk when my colleague Bernardo Schepop and I were presenting the semente project at a conference on Critical Infrastructures in Amsterdam in 2023. Bernardo is a designer who participated in the early stages of conceiving what would become the MetaReciclagem network, back in 2002 in Brazil. We reconnected twenty years later when I was planning a new phase in a series of collaborations between the University of Bristol, the Neos Institute in Brazil, and Brazilian initiatives that are reference points in working with technology in communities. Since then, I have been working with Bernardo on several projects, semente being chief among them.

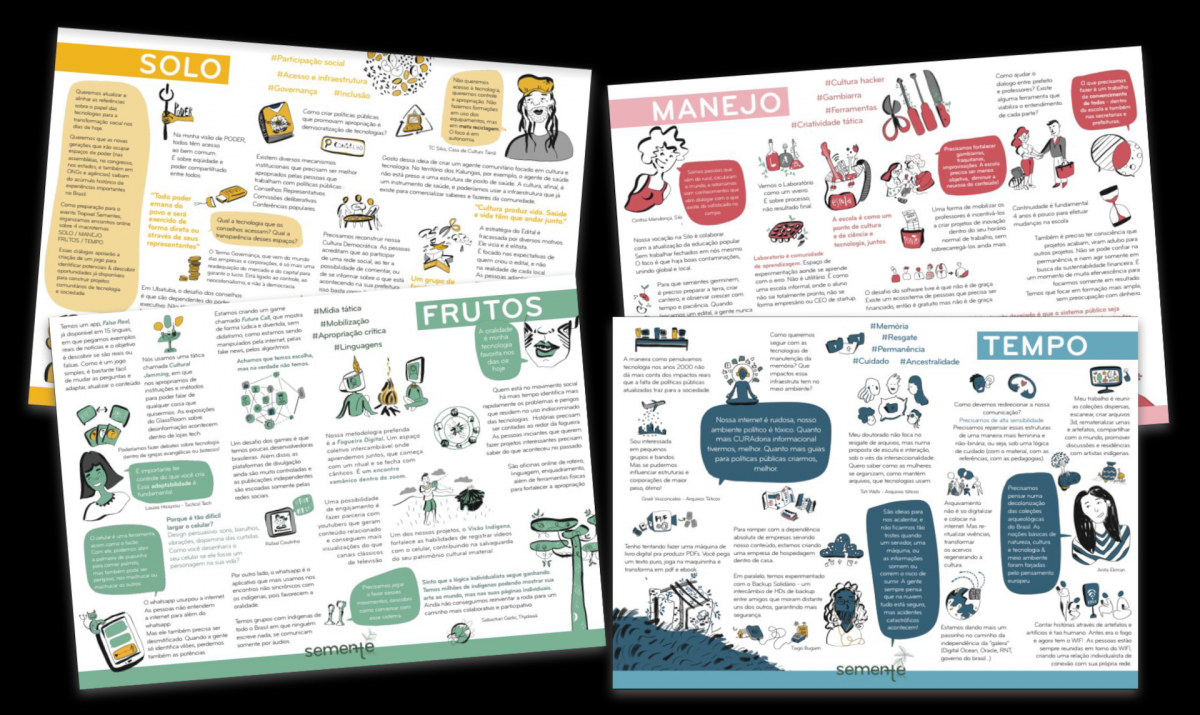

Semente is a collaborative tool for advancing community initiatives. We are working to distil decades of experience in open, people-centred, and participatory projects into a format for straightforward application. It builds upon previous work, especially the ID21 study and the fonte.wiki repository. At its core, semente prompts people to reflect on four perspectives that, we believe, should be part of every attempt to develop ideas and desires in the community: soil (foundations, preconditions, prior experience), handling (practices, tactics, and their adaptations based on environmental observation and changes), time (cycles, memory, documentation, and planning for future generations), and fruits (expected outcomes, how to measure them and assess their impact).

Macro areas of semente.

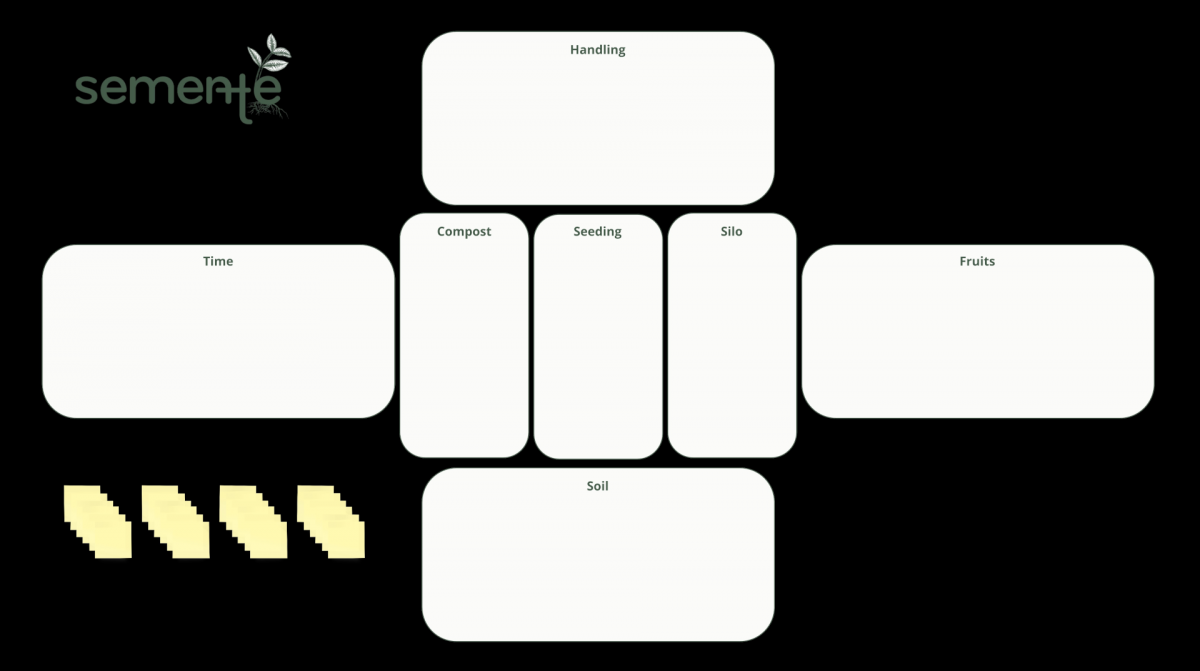

We designed semente to be a dynamic and iterative method. It is currently shaped as a canvas in which those four macro areas (soil, handling, time, fruits) are set – to help map and project conditions, desires, long-term commitments and relations to what lies outside the community. The canvas can be approached in any order. At its centre, the other three areas aid in defining the particular identity of the initiative, or its seed:

- Compost is where we put all the decisions that can not yet be made. Points in which consensus is lacking, aspects that require more data to be collected, or factors outside the community that still need time, observation, and learning.

- Seeding is the heart of the community, so to speak. Here we describe who the community is in direct and indirect terms, what are its boundaries, how it sees itself.

- Silo is the place to preserve elements for later. Such elements can take many forms: accomplishments, principles, ethos to uphold, limits the community won’t overstep.

The semente canvas (November 2023 version).

Beyond the name itself – semente is Portuguese for “seed” – the areas of the canvas echo, obviously, the choice of a set of analogies that refer to cultivation, care for plants, and the regeneration of nature. We had a first round of methodology tests in July 2022 during the Tropixel Semente Festival, in Brazil. Tropixel is an open space for critical discussion and building of alternatives connecting society, nature, and technology. Through a series of interactive sessions at that time, we collected feedback from participants coming from quite diverse walks of life.

Those sessions left us with doubts about whether to keep using analogies coming from vegetable cultivation and care. Would that approach condition the use of the tool to possibly cartoonish depictions of gardening? For some time, I accepted this question as unresolved and allowed myself to reflect further. It was only during the event in Amsterdam almost one year later, however, that I realised the importance of reaffirming these botanical metaphors that are also cultural – in the very sense of “culture” as cultivation: collective care for the continuous reproduction of conditions for life.

Graphic documentation of Tropixel Semente by Marina Nicolaiewsky.

The idea of thinking about technology and culture as supporting the emergence and regeneration of life is not new, of course. As one among many possible examples: nearly a decade ago, Luciana Fleischman and I conducted a study on experimental digital culture – available here, in Portuguese. One of the interviewees for that study, Jorge Bejarano Barco from the Museum of Modern Art in Medellín, stated that it is impossible to promote innovation without first fertilising the creative ecosystem. It is interesting to think about what this image – soil fertilisation – can suggest based on one of the strongest commonalities between Brazil and Colombia: the Amazon rainforest. Science says that the soil under the Amazon is relatively poor in nutrients, which surprises anyone who has had contact with that dense and vibrant ecosystem.

What keeps the forest in continuous reproduction are not the pre-existing physico-chemical conditions in the earth below it but the ongoing transformation of organic matter into nutrients enabling the emergence of new life – an accelerated, constant, whilst arguably superficial and precarious cycle. And yet, the forest is there, dense and active, recognised as a fundamental asset for maintaining life in Latin America and the whole planet. This superficial layer of organic matter is called in Portuguese serrapilheira (“plant litter” in English, according to Wikipedia). Many forest restoration projects adopt a strategy to restore vegetation in stages. They start using low-growing species with a rapid life cycle that protects the soil and creates basic conditions – plant litter – that will later enable the introduction of larger species.

On the other hand, it is always important to remember that the other humid forest in Brazil, the Atlantic Forest, does not achieve the same international prestige. Sadly, not even within the country. The estimates vary slightly, but it is a fact that around 90% of the original area of Mata Atlântica – which used to cover a large part of the Brazilian coast and extended so deeply inland that it reached over a thousand kilometres in, by the borders of present-day Paraguay – no longer exists as a forest. It went through centuries of destruction and species replacement, land grabbing, illegal occupations, and successive waves of exporting soil nutrients in the form of sugarcane, coffee, milk, soybeans, beef, and other commodities. Areas that used to be covered by dense multi-species forests have been transformed into mono-culture plantations for export. The effects of climate change have long been a concrete reality in inland cities in Brazil, which have become hotter and more prone to extreme events. This is a direct consequence of replacing the dense, diverse, and humid Atlantic Forest with what is sometimes called a green desert – hectares and hectares where only one species is cultivated. And yet, the less than 10% remaining area of the Atlantic Forest harbours a number of animal and plant species greater than the entire European continent.

Analogies can certainly be superficial and lead to distortions or over-simplification. On the other hand, when used consciously, they serve as a way to provide perspective, organise thoughts, and seek inspiration from different knowledge areas, allowing us to find alternative ways of approaching situations. By employing cultivation and regeneration as central metaphors for semente, we are not merely thinking about recreational backyard gardening with seeds bought from grocery stores in industrial packages.

I recall a discussion among several people participating in the Tropixel network, among whom I highlight the contribution of Fabs, Fabianne Balvedi. The topic was digital permaculture, a theme that had emerged in other networks related to Tropixel and that Fabs brought to the table. We discussed the limits of the analogy of “gardening” (which, I admit, we used quite a bit in the past when discussing the daily work of editing and maintaining the content of wiki sites). Illustratively, in 2022 a European diplomat suggested that Europe was a “garden” and the rest of the world a “jungle” trying to invade it. In this context, I obviously cheer for the jungle.

Quite to the point, that enclosed form of gardening as something imposed onto the environment by human hands, taking the form of an artificial construct to isolate itself from nature, does not work for what we intend to develop with semente. We are more interested in drawing inspiration from integrated and systemic perspectives – permaculture, agroforestry, and bioregional thinking that integrates city, countryside, and nature.

That is the backdrop of our contribution to regenerating public technology policies with a focus on communities. Metaphorically, the seed is but a small piece in a complex scenario. It should be understood as an elementary unit for conserving and propagating the genetic diversity of certain plant species. It is important to emphasise this: the seed does not create clones. It is not about automatically replicating the DNA of a specimen, in the sense that some mistakenly interpret it with images like the “selfish gene”. It is not about DNA conservation, but rather it's remixing with the present environment. The seed speaks of diversity and multiplicity, not repetition. It is an element of memory and rebirth, connecting all previous generations with the current development conditions: soil, water, sunlight, among others.

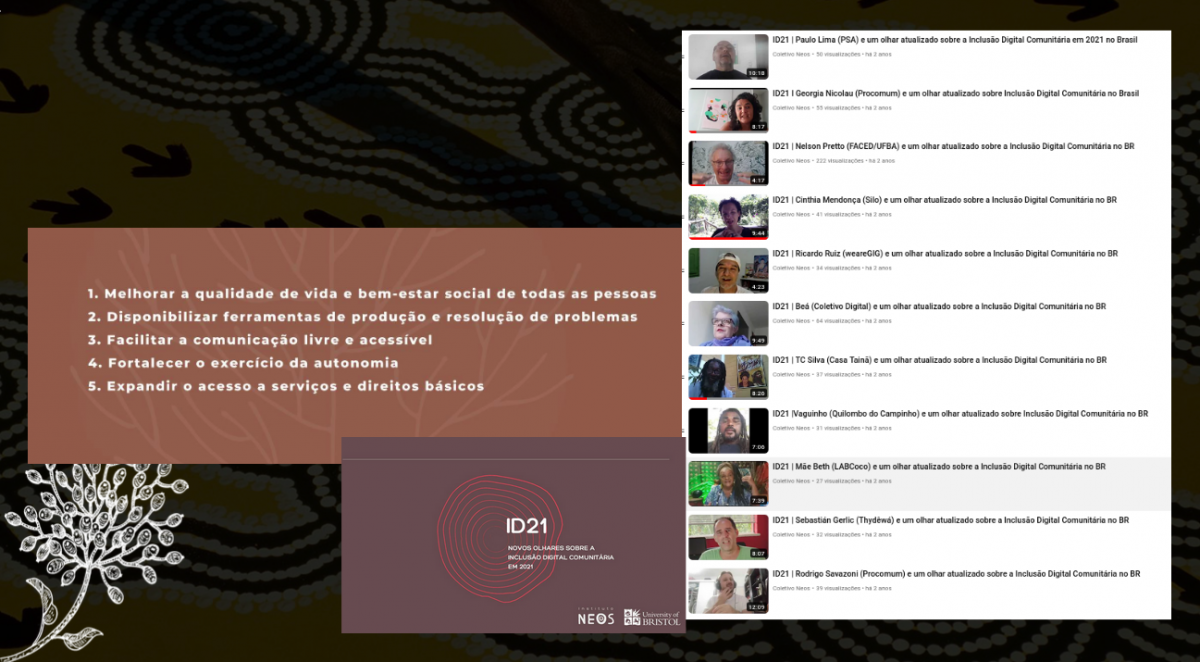

The semente toolkit emerged from a process that started three years earlier amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, the University of Bristol was interested in understanding the landscape of media appropriation and digital technologies in Brazil to inform a creative project that was being conceptualised. To meet that expectation, I assisted the Neos Institute in Brazil in designing and managing a survey in which we conducted short interviews with key individuals who had been involved in various initiatives of what was called “digital inclusion” in the early 2000s.

The interviews with those individuals shed light on the importance of discussing the consequences of the dismantling of public policies in the years since the political coup in 2016. In the project report, titled ID21, this absence of policy was one of the most striking points. It is important to remember that in 2021, Brazil was governed by an extremist regime with authoritarian aspirations, which rejected much of what had been developed previously in fields related to human rights, social inclusion, and cultural diversity. Development policies for Brazilian digital culture, social participation, and representation of differences no longer had the institutional support they had previously enjoyed.

ID21 study. Report available here (PDF, Portuguese).

What made me realise the relevance of insisting on the agro/botanical analogies of the semente project during the event in Amsterdam was precisely the fact that, when presenting it in an international context, I saw myself referring to that period of policy dismantling in Brazil as one of desertification. I also suggested that the multitude of initiatives that had developed there, mainly between 2002 and 2012, was, in contrast, a forest of initiatives.

It is important to emphasise this image again: at that time, we did not have a well-tended garden or a monocultural plantation of projects. It was a complex forest surviving through movement and invention, thus surpassing precariousness. There was a lot of experimentation, we made many mistakes, a lot of intentions did not take root. And yet, even though many of the people involved suffered the effects of a lack of predictability, bureaucratic difficulties, the absence of an overarching strategic vision, and competition for scarce resources, all while combating idea thieves and ill-intentioned opportunists, still there was a continuous creation of life, the building of symbiotic alliances, flourishing where least expected.

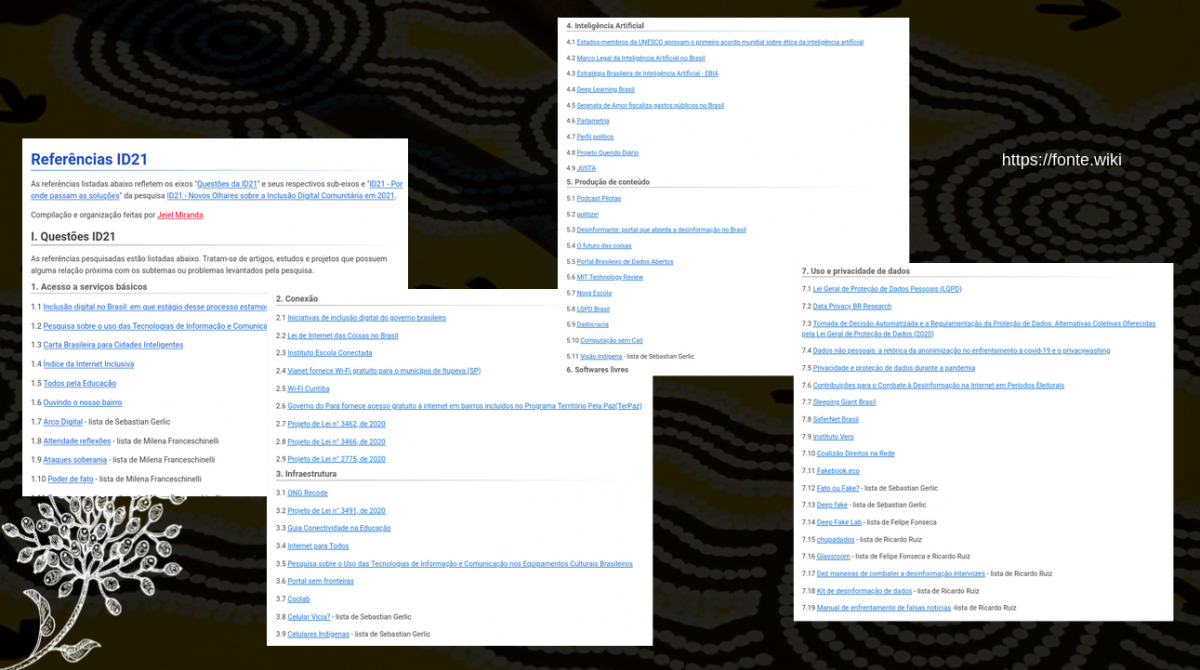

The following stage of cooperation between Neos Institute and the University of Bristol aimed at responding to another condition: the involuntary evanescence of collective memory. We suffered the disruption of access to the online portal of Brazilian digital culture, where numerous projects had documented their processes and discoveries, references, and productions. To investigate the question of what remained of those initiatives of digital inclusion, we created the online repository fonte.wiki. There, we set out to prototype an environment to organise and share lists of references and content that serve as a basis for many projects interested in community-based digital public policies.

Obviously, the choice of the term fonte (Portuguese for “source”) evokes the role that free and open-source software played in the origins of Brazilian digital culture. But the fonte in Portuguese can also be read as “water fountain” – the constant supply of water, capable of countering desertification if properly managed.

Sample of contents in fonte.wiki

Recently, many initiatives have emerged that aim to help people – even those with limited technical knowledge – understand how technologies work, the implications they have in our lives, and how we can minimally mitigate the risks they bring forth. These initiatives are of utmost importance, focused on individual and collective defence and protection. In the context of the analogies I am discussing in this text, I can see them as conservation initiatives. However, one must wonder how to go beyond mere conservation and move towards regeneration, reforestation, and valuing what escapes the framework of gardening and mono-culture.

With semente, we take a different path from many open methods for building technology-based projects that assume the need for a project leader. We equate such a character with the prototypical gardener – usually a man, white, educated, with knowledge of multiple languages and ties to powerful individuals – who convinces the world to help care for the outcomes of his store-bought seeds, whilst killing wild species and other competitors. Our bet, on the other hand, is to always start observing and creating relationships, discovering who the community is in all its diversity of knowledge, aspirations, and levels of involvement – our dense and complex forest – to collectively build what we want to be together.

We propose to think of community in a broad sense. Not a group that shares a single common trait – geographical, ethnic, religious – but a combination of multiple and diverse commonalities. To accomplish this, we need to create connections between multiple species and understand that it takes time. Tall trees cannot exist without the prior presence of fungi, ground cover vegetation, shrubs, and smaller trees, as well as microorganisms, insects, fish, birds, and other animal species. As far as metaphors go, we are aware that not all plant species propagate through seeds. Still, we insist on the relevance of developing methods that help understand the conditions and act on them. Our seed – semente – is one such experiment.

PS: An earlier version of this text was submitted in 2023 to be published in an edition of Facta Magazine, edited by Fred Paulino. As conversations and experiments with semente evolved, however, I felt like updating some parts of the text. My special thanks to Sofia Galvão Lima for the feedback that triggered some of these updates.